On December 23, 1919, Robert Ball was returning to his office at the Gallatin Democrat when he heard his partner shout “You won’t do that!” He looked to his right and saw co-publisher, Wesley Robertson, standing in front of his massive roll top desk. He watched helplessly as Gallatin City Clerk Hugh Tarwater pulled out a 32 caliber revolver and shot Robertson in the chest.

Tarwater immediately turned the still-smoking gun towards Ball in a rage, and yelled “Now Damned you I’ll shoot you too!” Two men ran from the back of the shop to help disarm Tarwater. During their struggle for the weapon, two more shots rang out, one of them lighting Robertson’s coat on fire. As they unsuccessfully struggled to subdue the shooter, Constable Ben Houghton arrived and Tarwater quickly handed over the gun. Houghton loaded Tarwater into his police car, and took him home.

The dying Robertson was taken a few blocks away to his home, and before succumbing to the shot that had lodged near his lung, he managed to give a coherent statement of what had occurred. Robertson stated, in labored gasps, that “Tarwater told me…..not to publish….or utter….his name….again. I told him….I would run….the paper to suit….myself…..He…..demands….and then fired.” Wes Robertson, 70 years old, died around 7:00 pm, just two hours after the shooting.

Ball had been surprised to see the event unfold – but was not shocked. The shooting was the culmination of a four-year feud between Tarwater and the Gallatin Democrat. Newspapers at that time unabashedly worked towards their own agendas and used their voice to influence events towards “the betterment of their readers.” The Democrat published strong, sometimes caustic editorials in support of prohibition and pursued stories to expose local political corruption. Bob Ball authored the Democrat’s editorial columns each week, and he took no prisoners. Tarwater was more than once the target of these scathing pieces.

The feud was ignited in 1914 when the Democrat published that City Clerk Hugh Tarwater had been charged with “consumption of intoxicating liquor and issuing blasphemous words.” This was particularly relevant because Daviess County had voted itself “dry” in 1907, some 13 years before the entire country adoped prohibition. As stated in the Democrat:

Informations charging Hugh Tarwater with being intoxicated and using abusive language were filed with Judge John Everman the first of the week. Under protest, Mr. Tarwater pleaded guilty to the former charge and was fined $20 an costs, no favor being asked or clemency extended by reason of Mr. Tarwater being official court clerk. The second charge will come up for hearing later. We understand Mr. Tarwater claims the charges were the result of his activity in helping round up gamblers and bootleggers.

Gallatin Democrat

Tarwater vehemently denied that he had pleaded guilty to the charge and demanded a retraction. The paper admitted that there was no record of any guilty plea in the court records, but claimed that the absence of records only proved that Tarwater was drunk AND corrupt.

As City Clerk, it was Tarwater’s job to file his own criminal paperwork in the court record. The paper claimed that he must have abused his office and neglected to file his guilty plea and accompanying papers. The allegation of the guilty plea, along with the compounded claims that he had abused his office, led Tarwater to file a suit for libel against the Democrat seeking $20,000 for injury to his reputation. Adjusted for today’s inflation, that would equate to around $320,000.

After the libel suit was filed, the paper’s scrutiny and comment about Tarwater only increased. He was the subject of consistent criticism and even mockery.

One of the events thought to have escalated tensions occurred during the 1919 Daviess County Chautauqua, held in Dockery Park, late August 1919. Robertson was on the Chautauqua planning committee, and when a scheduled speaker failed to appear, he stood in for the absent speaker as an impromptu substitute. He began his remarks by putting his thumbs in his vest, leaning back, and with a wry smile declared: “If I had known I would be called upon to speak, I would have worn my $20,000 suit.” The entire town was well aware of the paper’s feud and lawsuit with Tarwater, and they roared with laughter. Tarwater was in that crowd and was less amused. He stalked away, seething.

To be fair, Hugh Tarwater was an easy target. He was also his own worst enemy. It was common knowledge that Tarwater had “a problem with the drink.” He had been institutionalized in the St. Joseph psychiatric ward in February and again in June of 1896. His condition was described by doctors at the facility as “unusually suspicious and depressed and while in this condition would arm himself against imaginary enemies.” After a short stay each time, he was deemed “cured” and released. There were no facilities for alcoholism at the turn of the century, and asylums often served that purpose.

Tarwater’s defense attorneys later attributed the “constant nagging” and pressure from the paper as a factor that seemed to drive him into a downward spiral, deepening his alcoholism and associated mental delusions. Mrs. Tarwater testified during her husband’s trial that the 2 nights prior to the shooting, her husband had sprung out of bed in the middle of the night, “sezed his revolver” claiming to see the faces of Robert Ball and some of the attorneys against him in his libel suit peering in through his windows. He fired his gun outside his home (on South Street in Gallatin) several times before finally going back to bed.

The next day, he had written a letter to his attorney claiming that Ball and two other men had followed him home the Saturday before the murder and that he had “opened fire to scare them away.” He also stated that he had just sent his daughter 2000 miles away for her protection and that his wife and son “[didn’t] know the war… raging every hour in my heart, nor what a struggle it is to me to ward off mental collapse.” The stage seemed to be custom made for a bad ending. Tarwater was not just an alcoholic, but a paranoid and delusional alcoholic, with someone now actually out to get him – at least via his reputation.

On Friday, December 26, a coroner’s inquest into the shooting and Wes Robertson’s funeral were both held at 2:00 pm, within blocks of one another. The inquest, on the third floor of the courthouse, concluded that Hugh Tarwater would be charged with First Degree Murder. The funeral was held at the Methodist Church in Gallatin. The editor of the Jameson Gem said: “It was the biggest funeral service I ever saw.” Robert Ball eulogized Robertson, and in part, said:

In the big, kind heart of Wes Robertson, personal animosity and malice never found lodgment. There may have been other characters like him; there may have been other men as good as he, but in our lifetime we have never known them.

Robert Ball

Hugh Tarwater was tried for murder in Gallatin on October 4, 1920.

During the trial, questions arose about knowledge and/or peripheral involvement of the Daviess County Sheriff, J.A. “Atch” Blair. Blair was a Republican and had no fondness for the Gallatin Democrat or its publishers. It was widely said that Tarwater had spent the bulk of the afternoon of the shooting drinking at the Sheriff’s office, and went immediately from there to the Democrat, gun in pocket. Within a day of the shooting, Sheriff Blair publicly stated that it was “probable that Tarwater shot in self-defense…Robertson might have reached toward his desk for a gun just before he was shot down.”

Even more damning, a reporter later found himself in Sheriff Blair’s company on the Rock Island train headed for Gallatin from St. Joseph. Blair was unaware that the fellow was a reporter, and gave the stranger his opinion about the killing, saying: “One, I hate all Democrats, two, Tarwater done this state and the party a great service by killing the fire-eating Democratic editor.” No evidence of actual complicity by the Sheriff was ever alleged, but it was certainly thought that he may have helped push a man on the brink of sanity towards the ugly deed. The prosecutor successfully moved to have the Sheriff removed from any participation in the Tarwater’s prosecution.

Tarwater offered defenses of self-defense, insanity, and of having acted under passion and prejudice (temporary insanity). In short, the jury believed he was drunk, not insane, found him guilty of premeditated, first degree murder, and sentenced him to 35 years. Tarwater later appealed on many procedural grounds, but also appealed the fact that the prosecution displayed the victim’s bloodied clothing during the course of the trial by draping it over the jury box railing. His appeal was denied on all points.

Bob Ball sold the Gallatin Democrat, and moved to Colorado where he finished his life as an esteemed editor of a newspaper in Loveland Colorado. Tarwater made multiple attempts to apply for parole, and once even had a petition in support of his parole signed by more than 200 Daviess County citizens. All such requests were denied, and Tarwater died in custody.

The writers would like to thank Ms. Kate McCarty, daughter of former Gallatin North Missourian newspaper editor, Joe Snyder, for her input, as well as acknowledge the valuable information contained in Mr. Snyder’s book, County Seat Paper. You can also follow Kate’s blog at https://countrynewspaper.com/

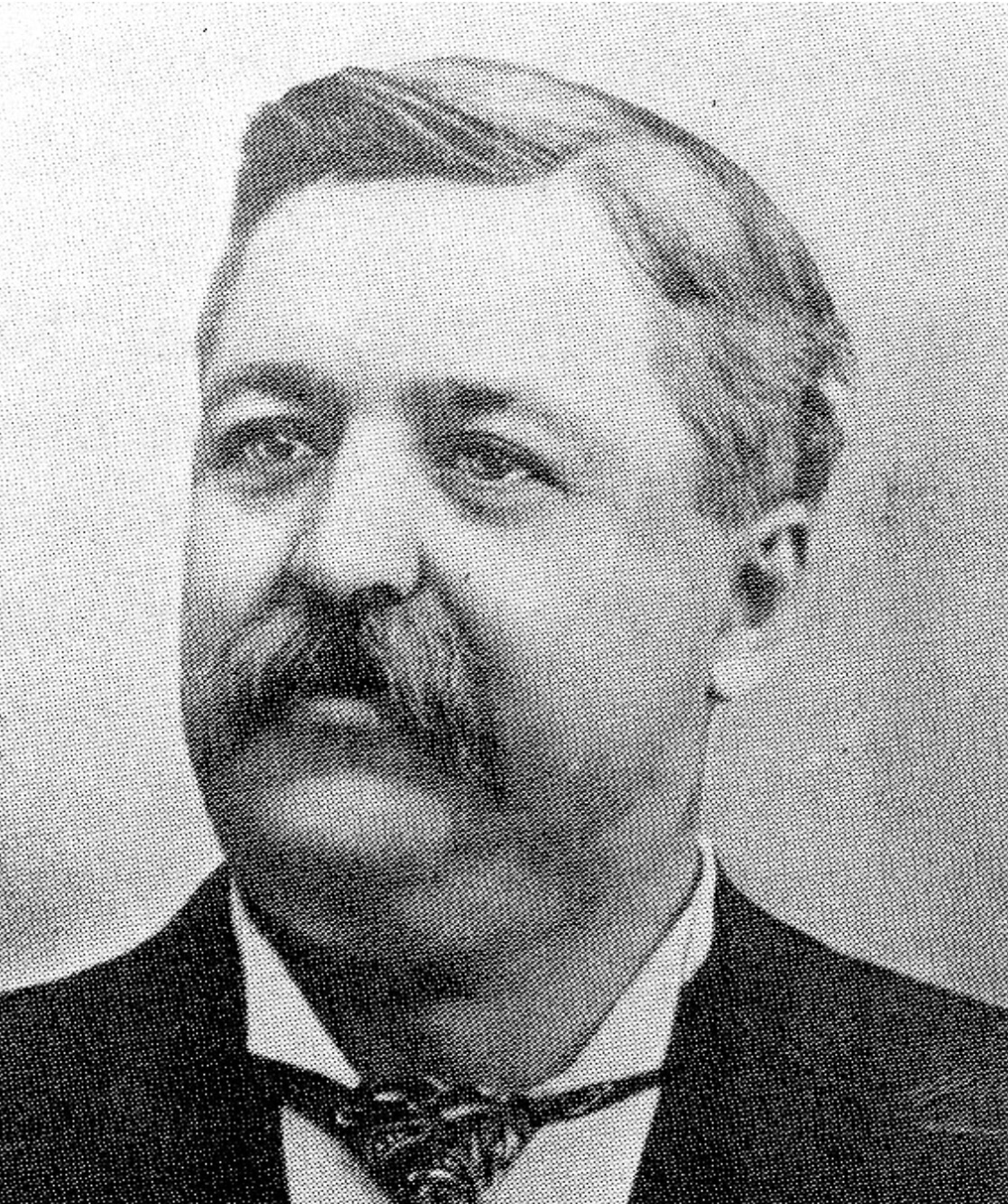

Wesley Roberstson, slain publisher of the Gallatin Democrat

Example of the gun used in the murder

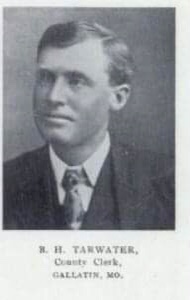

Gallatin City Clerk, Hugh Tarwater

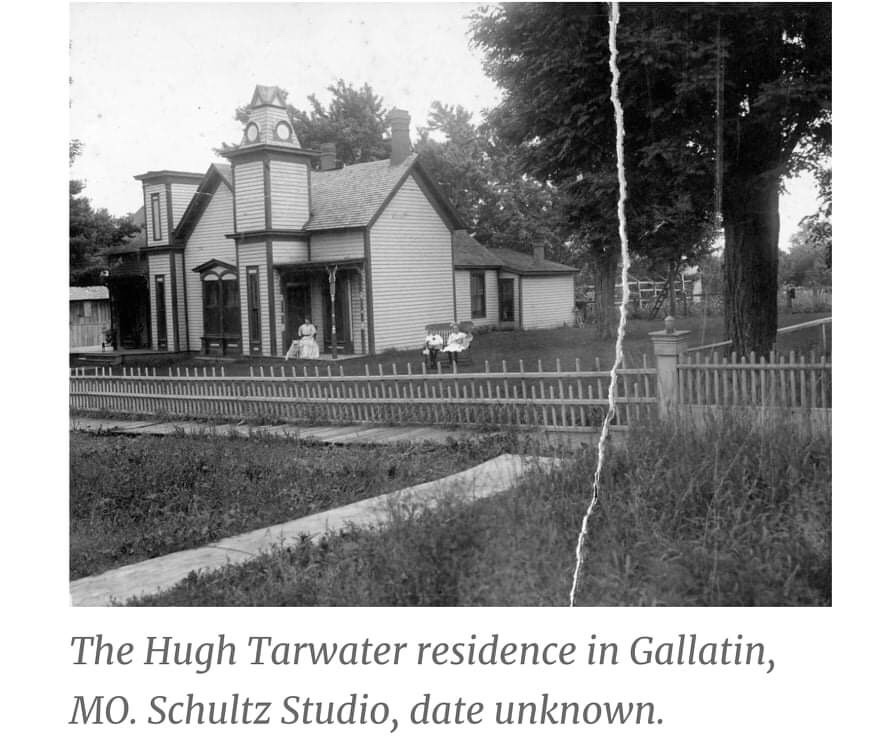

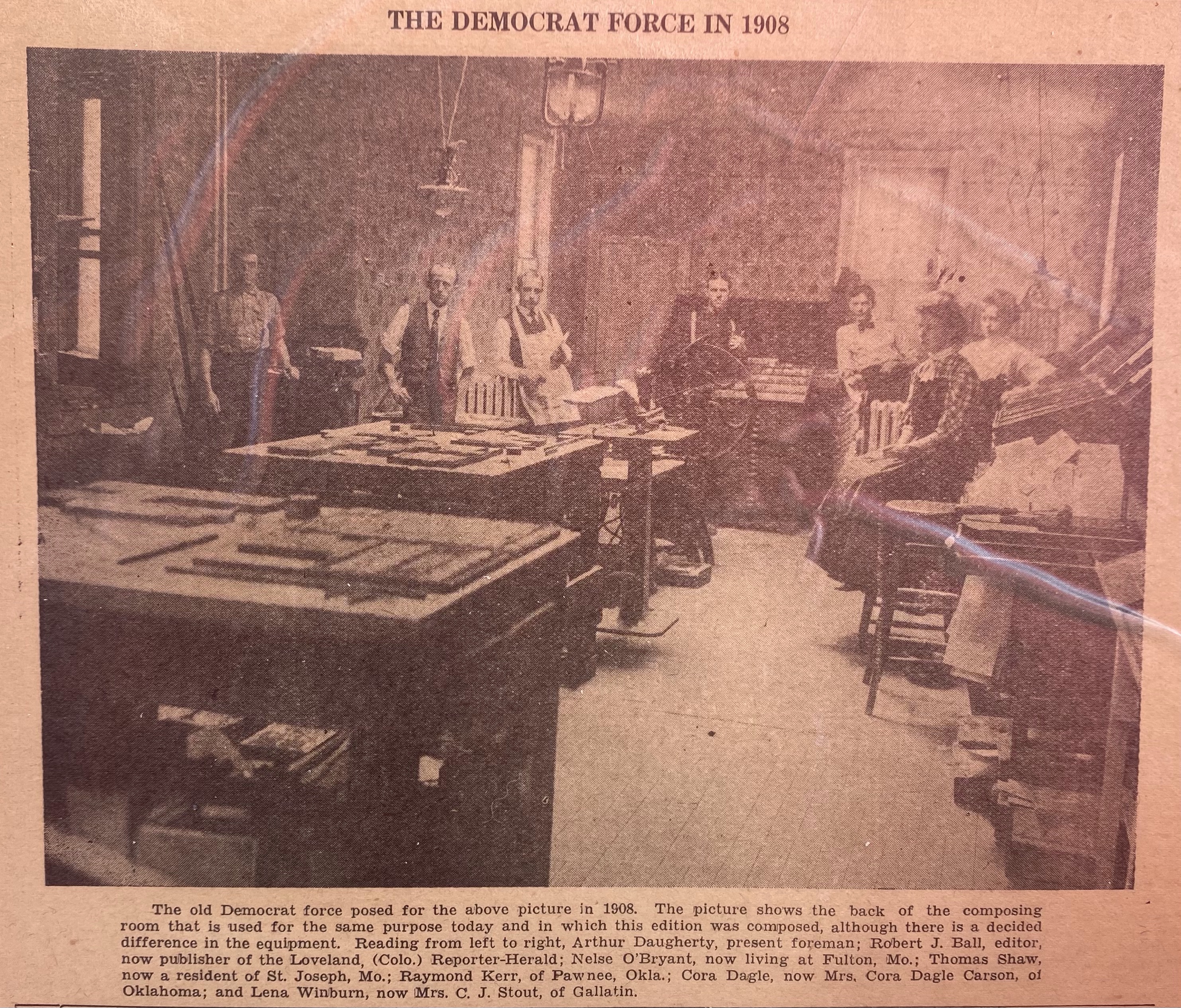

Wesley Robertson’s desk, used at the Gallatin Democrat. According to Kate McCarty, current owner of the desk, when they had the desk refinished, the workers said they could see the bloodstains. There also is evidence of a minor fire at some point, though it didn’t cause much damage.